Córdoba

and Medina Azahara

From

Úbeda we headed westward to Córdoba, where we spent the

next few nights. Along the way, we stopped at Baños de la Encina,

a sleepy village dominated by the huge Moorish fortress. After all,

this was the border between the Muslim south and the Christian north

for hundreds of years. Unfortunately, the fort was closed for renovations.

The

countryside around Baños de la Encina is really barren.

Córdoba

was once the capital of Moorish Spain, ruled from 756 to 1031 by a

caliph who was a descendant of Muhammad's family. Its old city still

has many of the buildings built by the caliphs set amidst narrow streets

of whitewashed houses.

We

told you they were narrow streets! (We had to drive our rented car down this

street

to park it, a feat Brian accomplished only by closing the sideview mirrors and

inching along

while having Joe and Matt navigate from outside in front of the two sides of

the car.

Large

sections of the Moorish town walls survive--and, on the left, a town gate.

As

elsewhere throughout the south, Muslim mosques were converted to Christian churches.

In most cases, the original buildings were demolished, but often--as in these

examples--

the minarets (towers from which Muslims are called to prayer) were converted

into church towers.

Córdoba

was renowned under its caliphs as a center of higher education. Among its best

known teachers were the

Muslim Abu Ali ibn Sina (known in Christian Europe as Avicenna) and the Jew

Moses ben Maimon (known as

Maimonides), both of whom taught philosophy, theology, and medicine. Modern

Córdoba commemorates

both with statues, Avicenna on the left and Maimonides on the right (from different

parts of the city).

After

the Christian conquest of Córdoba in 1236, a large medieval fortress

called the Alcázar

was built, which also served as the royal residence whenever the kings of Spain

visited the city.

Lots

of bits and pieces of the Moorish tradition survive in architecture, often--as

in these examples--mixed with

other styles. On the left, the typical horseshoe arch is surmounted by a Renaissance

portal. On the right,

the entryway and lower story window are Moorish while the upper story windows

are Gothic.

The

jewel of Córdoba is without question its former mosque, still called

the Great Mosque of Córdoba

even though it was converted into a Christian cathedral in the thirteenth century.

From

the exterior, the mosque appears as a huge square building. On some sides, little

decoration has survived.

On

the western side, however, most of the doorways retain their embellishments.

The

artistry of sculpture around these doorways is incredible. (In the Muslim religious

tradition, it is forbidden

to represent human figures or even living things, so Muslim artists have long

excelled at geometrical design.)

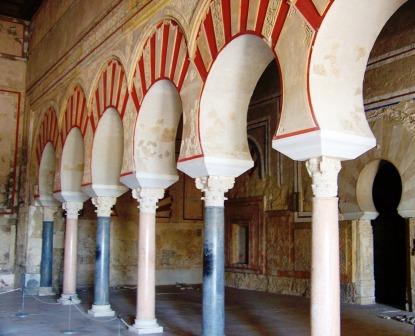

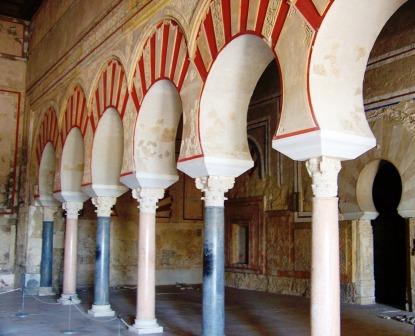

The

beauty of the exterior pales in comparison to the interior, where a forest of

columns--many of which were

Roman ones reused--is topped by two rows of arches, one atop the other. In a

typical feature of

this early Moorish architecture, the arches have alternating bands of painted

red and white stone.

There

are more than 850 columns--and the effect is dazzling. This original part of

the mosque was built in the eighth century.

To

this original structure were added in the tenth century wings in even more elaborate

styles--

multifaceted domes and multipointed arches. The opulence of the effect is overwhelming.

While

much of the mosque has been preserved as it was first built, even after it became

a church,

sadly beginning in 1523 parts of it were redone in more "Christian"

styles.

In

some areas, the flat ceiling above the double rows of arches was transformed

with Gothic tracery.

Other

areas were redone in Renaissance styles--with coffered ceilings, as on the left,

or painted frescoes, as on the right.

You

can see the effect best from a distance: its as if a Gothic cathedral were poking

out of the middle of the mosque.

Even

the minaret was transformed into a more traditional bell tower. On the right

is the entrance underneath the tower.

It

is still a spectacular monument--here, lit up at night.

Córdoba

is a vibrant modern city, too, with lots of attractive buildings from the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

We

happened to be there during Córdoba's annual fair

and saw lots of fairgoers in traditional Andalusian costume.

In

the tenth century, the greatest caliph of Córdoba, Abd al-Rahman III,

decided to leave his capital and, on a nearby hill, to build a palace for his

wife, Al-Zahra. Soon a town (called Medina al-Zahra by the Moors, and Medina

Alzahara in modern Spanish) sprang up around it. The place is now largely in

ruins, but is open to the public.

You

can see Córdoba in the distance from the ruins of Medina al-Zahra.

The

standing walls on even the collapsed buildings show off the horseshoe arches.

The

audience hall, where the caliph met his guests and visitors, has been partly

reconstructed.

Some

of the surviving details--such as the wall carvings--is stunning.

Elsewhere, the marble that once lined the walls and floors lies broken and scattered.

In

fact, the glory of Medina al-Zahra was shortlived. In 1010 (less than a hundred

years after it

was begun) it was sacked by Berber invaders from North Africa, and never again

inhabited.

Close

this page or click here to go to the next page.